Seattle Times: Black, Native infants in King County die at higher rate than white babies

February 27, 2023 10:41 amBy Alison Saldanha / Feb. 27, 2023

Every year, about 100 of the approximately 25,000 babies born in King County die before their first birthday.

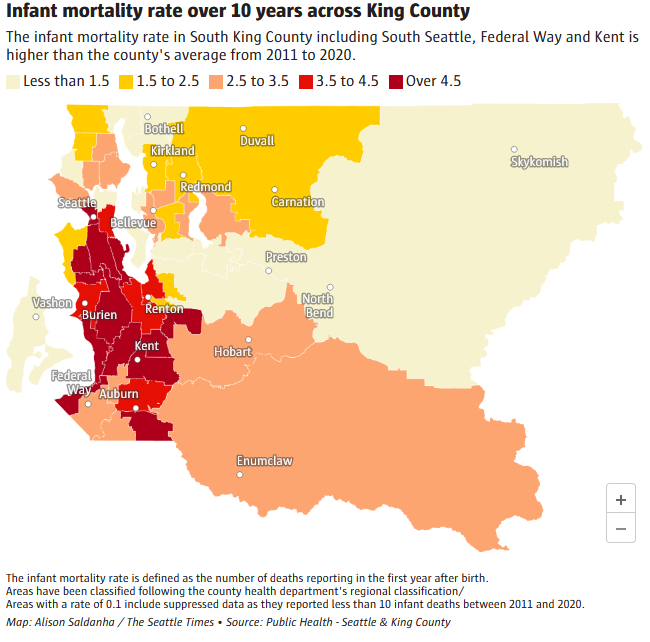

Most of those deaths, about 70%, are concentrated in the south end of the county — home to the poorest, most diverse neighborhoods, according to new data from Public Health – Seattle & King County.

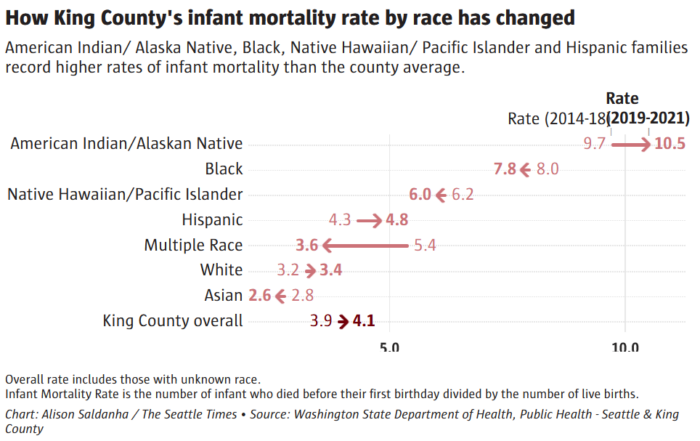

While King County’s overall infant mortality rate of 4.1 deaths per 1,000 births between 2019-2021 is below the national average rate of 5.4, according to CDC data, Black and Native babies are dying at a higher rate, one that is comparable to states that have the worst infant death rates in the U.S.

The deep disparities in infant deaths, widely used as a measure of population health, indicate the unmet needs of these communities. They not only reveal gaps in the health care system but also demonstrate how factors like socio-economic status and access to basics, including food and education, affect the overall welfare of the community.

Inequities in institutional support led Tara Lawal, a Native Hawaiian and Indo-Fijian midwife, to partner with Jodilyn Owen to start the Rainier Valley Birth and Health Center in 2015. The center serves families in the Rainer Valley and South King County, offering free, culturally relevant health care including home visits, birth and postpartum doulas, and lactation support regardless of the family’s insurance coverage or ability to pay.

“We’re a mile down from Seward Park; you just go down on the hill and you don’t have to look far for the disparities. They’re here,” Lawal said.

She said the volume of births managed at hospitals has led many families in these neighborhoods to feel isolated and intimidated as they navigate the health care system, adding that these experiences worsened during the pandemic.

At a Feb. 16 King County Board of Health meeting, Dila Perera, executive director of Open Arms Perinatal Services, spoke about the benefits of individualized care, particularly as it applies to people from marginalized communities. For over two decades, Open Arms has served nearly 500 families annually.

Perera showed how Open Arms’ model of culturally relevant, personalized care had not only significantly improved health outcomes for Black and Native mothers and babies they served. Among Black and Native families under their care, the incidence of preterm births was half the county average, and mothers reporting lactation at 6 months or longer was nearly double.

“Community organizations like Open Arms will always be more nimble and flexible when it comes to meeting families in need as we are truly on the ground,” Perera said. “However, we need supportive allies in public health and local government to trust our work and approach, and fund such interventions outside as well as within public health.“

About 70% of infant deaths in King County happen during the first four weeks of life, according to the county health department. Birth defects, particularly congenital heart defects, are the leading cause, followed by maternal complications during birth.

The latest data further shows that babies born to Black parents and American Indian/Alaska Native parents are two and three times, respectively, more likely to die than babies born to white parents. The disparities are even greater when compared to babies born to Asian parents, a group that reports the lowest infant mortality rate in King County.

At 10.5, the infant mortality rate for American Indian/Alaska Native mothers in King County is much higher than the overall rate in Mississippi (8.12), ranked highest in the U.S. for infant mortality in 2020, according to the CDC.

The infant mortality rate of 7.8 for Black mothers in King County surpasses the overall rate in Louisiana, which ranked second in the U.S.

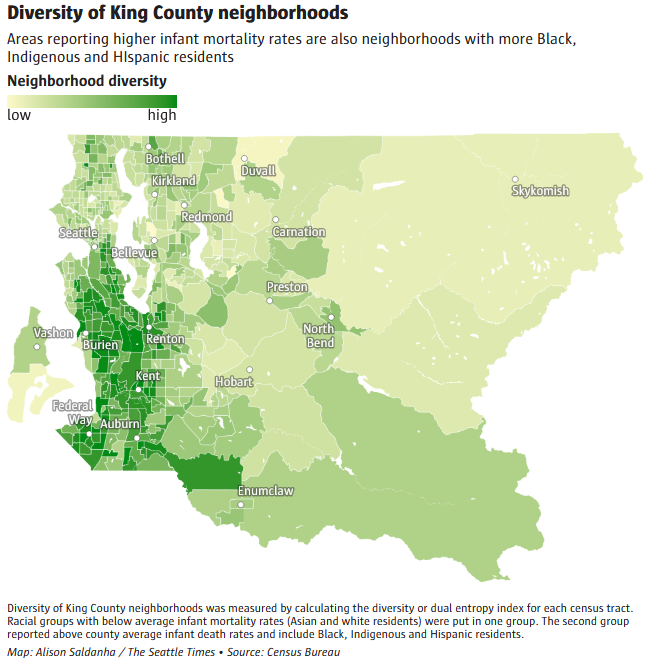

A spatial analysis by The Seattle Times of the 10-year average infant mortality in King County confirms how these disparities are spread. Neighborhoods with higher rates of infant mortality are more diverse than areas with lower death rates.

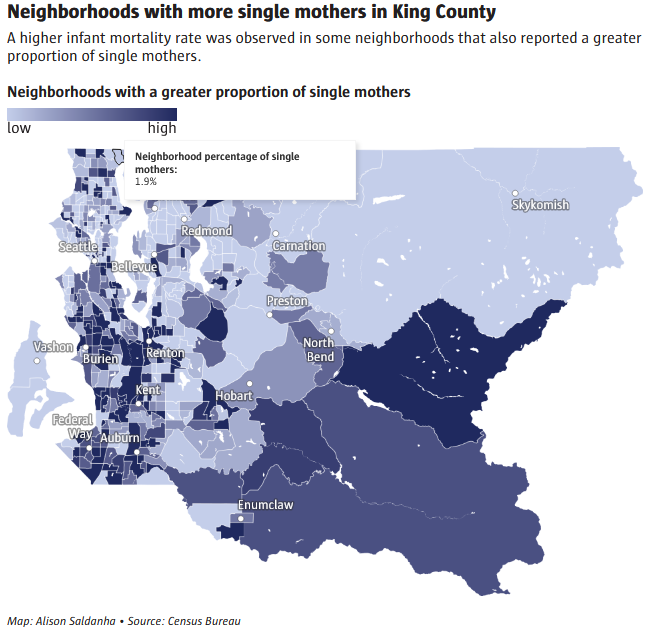

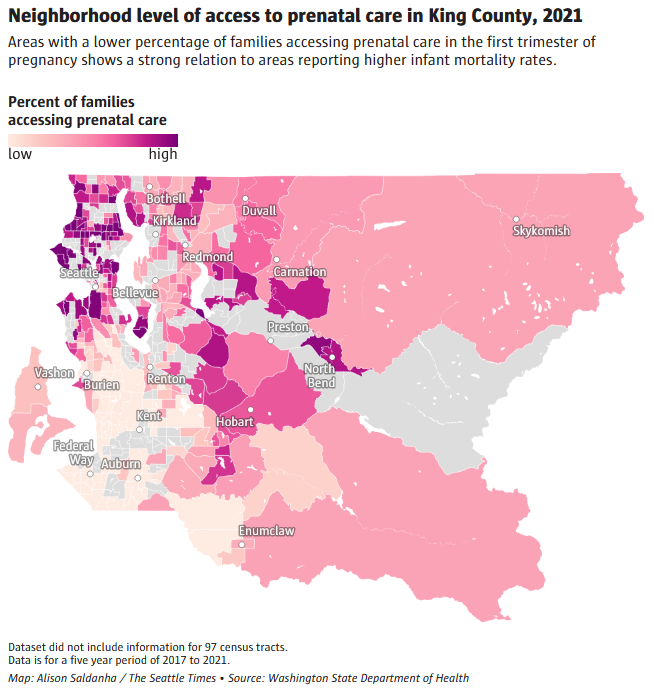

They are also much poorer. These neighborhoods have more single mothers with children under the age of 6, more food stamp recipients and alarmingly fewer families who get prenatal care.

Prenatal checkups are essential to avoid pregnancy complications and improve infant health. The low percentage of families accessing such care in these areas likely indicate fewer options for quality care for Black, Hispanic and Indigenous mothers-to-be, according to the county health department.

There’s also little to no focus on postpartum care, said Triniti Gorbunova, a lactation specialist at Rainier Valley Birth & Health Center.

Support services like WIC, the supplemental nutritional program for low-income women, infants and children, displace the culturally relevant care that recognizes the diets of different communities.

“We still don’t have enough health care providers asking informed questions,” Gorbunova said. Instead, families are told what to eat without any practical guidance based on their culture or the foods already in their pantries.

Communication gaps between the federal WIC program and the state’s First Steps program, which offers maternal and infant support services, have added to the barriers families face.

For example, it only takes a dollar to disqualify someone from WIC, said Michelle Sarju, administrator of Public Health – Seattle & King County’s Parent Child Health Programs, and many families have had to lose their services.

“Does that now mean with $1 over or even $1,000 a year, you have enough money to access the vast array of resources wealthy people access for babies? No, it doesn’t,” said Sarju, a midwife. “But that’s how the core system is set up and that’s what falling through the gaps looks like.”

WIC and First Steps are federal programs that local health departments can’t alter, Sarju said. “They have to be changed at the federal level, and they haven’t been changed in 30 years, though our world is vastly different now.”

In search of a solution, the county health department began designing a new program, Family Ways, in 2019. The pilot program, launched in fall 2022, is funded by the Best Starts levy, which was renewed in 2021. It works with and promotes community-based organizations to offer Black and Native families support during pregnancy, birth and early parenting — regardless of income.

“We needed one that wasn’t connected to having to generate revenue, but was literally designed to serve the people in the way they themselves had identified they needed to be served,” Sarju said.

For now, Family Ways is focused on supporting Black and Indigenous families. If other families approach the program for help, they will be connected to available resources.

Eva Wong, senior epidemiologist at the county health department, emphasized that while strong obstetric, prenatal and pediatric care are critical to improving infant health in vulnerable communities, care begins before conception.

“It’s not just the one visit that someone has three months before conception, it’s about when they’re a child, an infant, a child, a young adult themselves — food, housing, education,” said Wong.

Studies, including a 2021 report in the Journal of the American Medical Association, show infant mortality among babies born to Black mothers is linked to chronic stress accumulated over a lifetime of experiences of racial discrimination and systemic oppression, creating biological changes that affect the health of mothers and newborns.

Even the richest Black mothers and their babies are twice as likely to die as the richest white mothers and their babies, according to a new study of 2 million California births.

All of that is fundamental and foundational, Wong said. “So expecting it all to change in nine months of pregnancy is asking too much of prenatal care.”

Alison Saldanha reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

Read the original article in the Seattle Times.